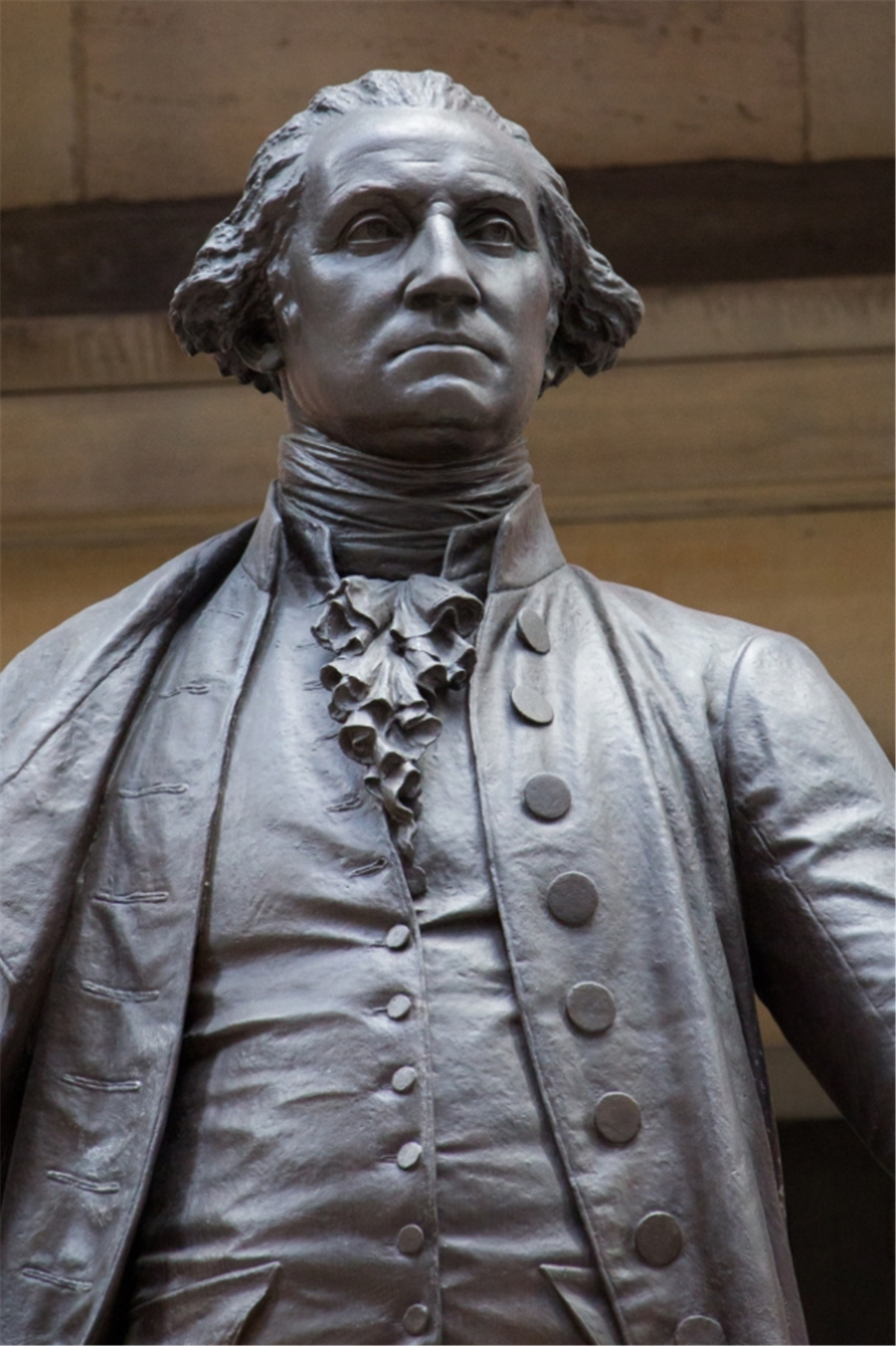

George Washington Reports on the Status of the War to Congress

Four thousand men commanded by Lord Cornwallis... were employed in foraging in the country adjacent to their posts. No distinction appeared in their manner of proceeding--property of every description, whether belonging to persons inimical to or favorable towards the British cause, was taken and carried off by them....

I am informed by Mr. Griffin, just from Boston, that this gentleman [General Burgoyne] either holds, or is inclined to hold, very different sentiments from those he lately professed on the power of these states; that he unreservedly declares that it is next to impossible for Britain to succeed in her views; that, when he returns home, he will with freedom declare his sentiments to the king and ministers; and that, he said, seemed to think that a recognition of our independence by the king and parliament would be an eligible measure, under the idea of a treaty of commerce on a large and comprehensive scale. How far these professions may be genuine, I am not able to determine, but, if so, what a mighty change!

Congress seems to have taken for granted a fact that is really not so. All the forage for the army has been constantly drawn from Bucks county and from Philadelphia county, and those parts of the Jerseys nearest the city; in consequence of which it is now nearly exhausted, and entirely so in the country below our lines. From these places also all the supplies of flour, that circumstances would admit of, have been drawn. In many cases the millers were averse to grind, either from disaffection or from their fears; this lessened the supplies, and the quantity that, with the assistance of the guards we placed over them, was compelled from them, was not great. As to stock, I do not know that any material supplies were obtained from thence; and whether any could be obtained I do not know.

I confess that I have felt myself under great embarrassment with respect to a vigorous exercise of military power. An ill-placed humanity perhaps, and reluctance to give pain, may have restrained me too much; but these were not all. I have been well sensible of that prevailing jealousy of military power, and that this has been, and still is, considered as an evil, much to be apprehended, even by the best and wisest among us. Under this idea I have been cautious, and wished to avoid as much as possible everything that might add the least shadow of foundation to it. However, Congress may depend upon it that no exertions, in my power to make, wanting due regard to the circumstances we are in, shall be wanting on my part, to keep the army sufficiently supplied on the one hand, and to prevent the enemy from getting supplies on the other.... I should be happy if the civil authority of the several states, under the recommendation of Congress, or of their own mere will, seeing the necessity of bringing into the common cause every possible means of obtaining food for the army, would always adopt the most spirited measures, suited to the end. The people at large are governed much by custom. They have been always taught to obey with implicit submission every act of legislation or civil authority, without reasoning on the propriety or impropriety of the thing--to military power, whether immediate or derived originally from another source, they have ever looked with an uneasy and jealous eye.

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Jerry

Jerry Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link