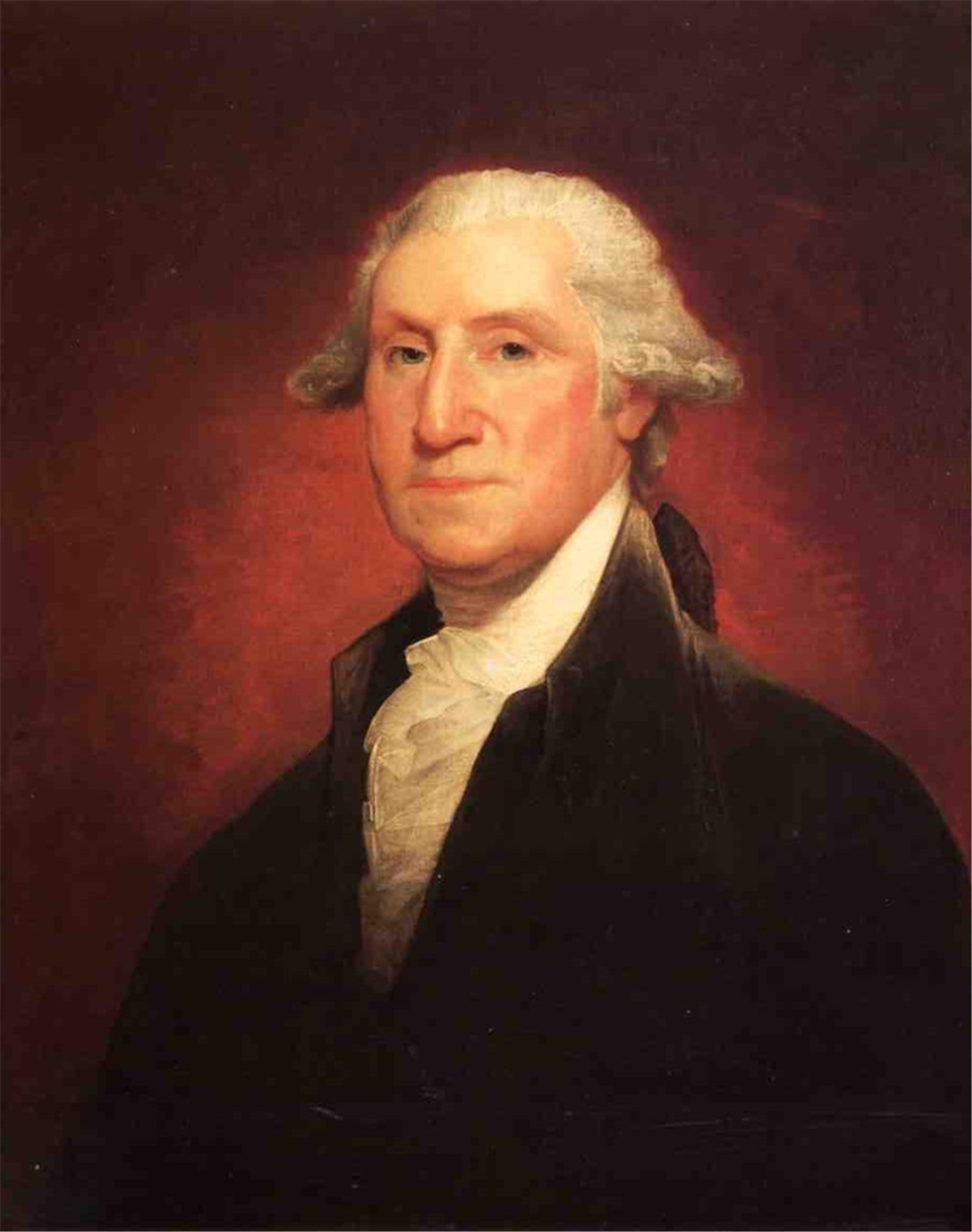

How George Washington made America great

As he trudged through wilderness with his surveyors’ instruments, there were many impediments that he pushed through besides tree limbs and tall grasses; he had to hack his way through personal doubts and insecurities regarding his future. He was, at this time, like a hewn marble block in the hands of a sculptor, awaiting being shaped and then refined and perfected; only he could not know when, how or even if that would ever happen. The big if was the operative word in his life. Insofar as his natural endowments were concerned, the physical part was developed; his commanding stature and presence had already manifested themselves. But he was still lacking in the area of the inner self, which could complement and enhance the outer self. It was this developmental growth that he set out to accomplish, and which, over a lifetime, he would do.

He could not have known that the George Washington who became a surveyor was to become the George Washington of the Tidewater plantations, and then transform into the George Washington “The Father of His Country,” the one who would be memorialized by Major-General Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee as “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” That appraisal would not come until a lifetime of accomplishments lay behind him, the greatest of which was defying an earthly monarch and the most powerful empire on earth in order to establish something that was never conceived before by the minds of men: a country composed of United States dedicated to the principle of democratic republicanism.

For a time, however, his aspirations did not rise to such lofty heights; his primary ambition was to be ruler over his dream plantation, Mount Vernon. But Destiny had another goal in mind for him; he would be the first President over his dream country, America. In between those two dreams, he would become, through a series of purposeful choices, the man we know today as the revolutionary who became his country’s first President, who, at the peak of victory and power, voluntarily resigned his high office, thereby establishing a precedent of selflessness and non-ambition for his office—something which no monarch or king of the past could ever conceive, much less do; this latter act would confound and bewilder his countrymen, not to mention that very king whom he had overthrown and defeated, both on military battlefields and the battlefields of ideas.

The title of the James Thomas Flexner biography succinctly describes him: The Indispensable Man. Indeed, he was indispensable to his country because he devoted his life to being indispensable to his country. He was able to hold the country together because he had a greater hold upon himself, for the simple reason that he was human. The stoic Washington had a great, almost volcanic temper that, if he had let loose, could have destroyed him. While being observant and perceptive, he was not as educated as his fellow Founders were, and, as such, he was embarrassed by that fact. Moreover, if he really knew what his fellow countrymen John Adams and Thomas Jefferson really thought of his intellectual capacities, they would have embarrassed him even more. Although he had a practical cast of mind, he could also be cunning when he had to be.

But it was his self-knowledge that saved him. That may have been his most important personal characteristic. Being self-aware of who he was, he did what he could to refine himself. Knowing what he didn’t know, he did what he could to educate himself. Knowing his self-doubts, he surrounded himself with his betters so that he could learn the “arts” of polite society and thus acquire those social graces he needed in order to be accepted and respected—and eventually emulated—in his society. So he studied, read, wrote and observed. As his greatness matured, he became more humble, modest and courteous. In all his affairs, he was patient and reserved. It was these real “weapons” that helped him win the many wars in his life, whether they were the battles on the battlefield or the battles in his own soul.

Before Mr. Washington could govern a nation, he had to govern himself. And throughout his life, he lived by certain precepts that he wrote down from time to time and often thought about. For example: “Be courteous to all, but intimate with few, and let those few be well tried before you give them your confidence. Observe good faith and justice toward all nations. Cultivate peace and harmony with all. The bosoms of men, when disturbed, are in general more prone to passion than reason. Guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism. Associate with men of good quality if you esteem your own reputation; for it is better to be alone than in bad company.” But perhaps the most revealing statement of all was his fervent desire: “I hope I shall possess firmness and virtue enough to maintain what I consider the most enviable of all titles, the character of an honest man.”

And just how would the “indispensable man” view his country today? What would he think of its accomplishments — and the intractable problems that still nag at our national conscience and seem to defy solution? And, more pointedly, what would he think of those who now seek to occupy the office he had once held with such dignity and respect — the office he once sought to endow with the mantle of “character”?

Of course, we can’t know what George Washington would do, say or think in our current circumstances, for we cannot evoke him forth from his final resting place in the soil of Mount Vernon. But we can do the “next best thing”: reapply the “weapons” he wielded throughout his life as a means of overcoming the adversities and challenges that always confront Americans: these being humility, modesty, civility, patience and reserve. In addition, he relied on faith to give him courage to find his way through life’s storms; these too should give us strength in our time in order to meet the challenges of the moment. These principles contributed to the shaping and forming of a man and a country; perhaps they can do so again. These were the lessons, the beacons of light that “The Father of His Country” bequeathed to his posterity—lessons we need to relearn if we wish to maintain the greatness he wanted his country to have before the eyes of mankind—and history.

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Jerry

Jerry Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link