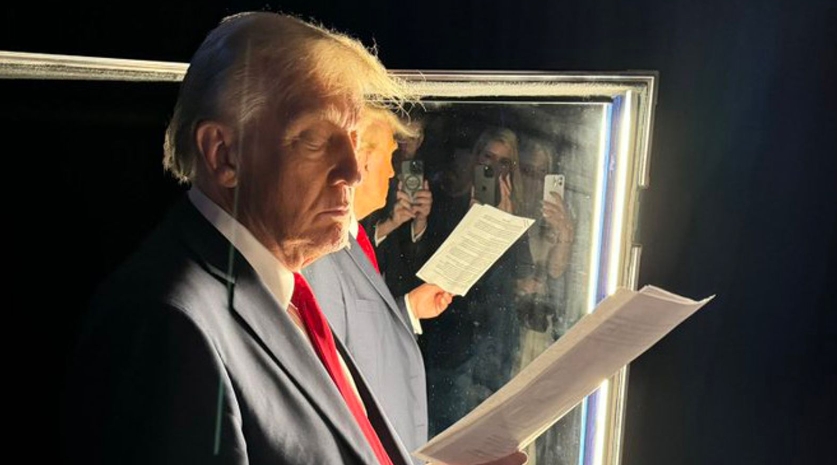

South Korea's Public Prosecutor's Office: Anyone who tried to stop the arrest of Yoon Suk-yeol could be prosecuted

Kim Dong-yeon, the chief of the Special Prosecutor's Office for High-Ranking Public Officials, said on January 1, 2025 that anyone who attempts to stop the arrest of South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol could face prosecution.

Earlier, Yoon said that an arrest warrant and a seizure search warrant, issued based on a request from an investigative agency without the authority to investigate treason, is illegal and invalid.

"Any obstacles that are set up and iron gates that are locked in order to hinder our execution of our arrest warrant will definitely be considered an abuse of power against public officials," Kim Dong-yeon was quoted by AFP as saying. "Anyone who does such things will be prosecuted."

Kim also said on Monday that his agency will execute the arrest warrant against Yoon within its validity.

South Korea's Seoul Western District Court issued an arrest warrant on December 31 for the impeached president, accusing him of inciting an "indignation" and abuse of power. The court also issued a warrant to search Yoon's presidential residence in Hannam-dong, central Seoul. This is the first time in South Korea's constitutional history that a sitting president has been issued an arrest warrant. Under South Korean law, arrest warrants usually last one week from the date of issuance. However, if an arrest warrant is not executed, its validity may be extended with the court's permission.

Yoon's defense team earlier said in a joint statement that the arrest warrant as well as the search warrant were illegally obtained and invalid since the investigation agency requesting them had no jurisdiction to investigate treason. According to Yoon's lawyers, the president's counsel plans to request a trial and an order to suspend the implementation of the arrest warrant at the country's constitutional court over concerns about the Special Prosecutor's authority.

Following three refusals to respond to a court's summons to be investigated for his involvement in treason, president Yoon Suk-yeol of South Korea received an arrest warrant on the last day of 2024, the South Korean court approved an arrest warrant on treason charges against Yoon, who has been impeached by the national assembly for ordering a martial law-style crackdown on opponents earlier this month.

According to South Korean news reports, the Seoul Western District Court also ordered a search warrant for the president's residence in Hannam-dong, central Seoul. Authorities are expected to send people to carry out the search there, according to the plan from the Special Prosecutor's Office for high-ranking public officials (SAWO).

The execution period of the order lasts until January 6, 2025, a week from now. SAWO's chief said on December 31 that the agency had not yet decided when the arresting order against Yoon would be enforced. Analysis said SAWO faced huge challenges on this enforcement. The current arrest law states that a suspect must appear in court to apply for a detention order within 48 hours of arrest, and that a person who is arrested may be detained for up to 20 days. However, given the limited police resources of this country, completing a detailed investigation of a case related to the president of a country in such a short period of time would be a challenge.

Why Does The Court Order An Arrest?

SAWO, comprising the Special Prosecutor's Office for High-Ranking Public Officials (SAWO), the National Police Agency, and a Defense Ministry investigative unit, petitioned the court on December 30 to issue a detention order for Yoon.

SAWO has previously sent Yoon three notices for questioning. However, Yoon refused to appear before investigators on December 18, 25, and 29 and responded with silence. According to South Korea's criminal procedural law, an arrest warrant could be granted for a criminal suspect who refuses to cooperate with questioning without good reason.

South Korea's National Assembly passed an impeachment motion to remove disgraced President Yoon from office in a vote on December 14, accusing him of abuse of power and ordering an attempted coup. According to South Korea's criminal procedural law, an arrest warrant could be granted for a criminal suspect who refuses to cooperate with questioning without good reason. But an important exception in the South Korean constitution: the nation's president enjoys legal immunity while in office. However, the exception does not extend to an impeached president or in cases of treason or external aggression.

Whether or not Yoon's treason allegations have been substantiated, and whether or not he is justified in refusing to answer to a summons without cause, would be reviewed by the court before issuing an arrest warrant. Given that Yoon was arrested, many analysts believe that the Seoul Western District Court accepted SAWO's assertion that Yoon had led an attempted putsch, and that this must be investigated through a forced summons.

Moreover, as South Korea's Yonhap news agency says, the arrest warrant was approved, partly because military and police personnel involved in alleged treason were arrested one-by-one at the direction of the Public Prosecutor's Office, and because Yoon's refusal to answer the summons was unconditional.

Yoon Suk-yeol Claims He is Entitled to Arrest Himself

Yoon's defense attorney Im Ghae-gun stated on December 31 that an arrest warrant sought by the Special Prosecutor's Office for High-Ranking Public Officials, an agency without authority regarding treason, "could not be a legitimate act." According to the lawyer, Yoon will file a petition with South Korea's constitutional court, alleging that SAWO's request was unconstitutional and unlawful, requesting that the court halt the implementation of and terminate the arrest warrant. Otherwise, he would argue, Yoon has the right to arrest himself.

According to the lawyer, "the current law on high-ranking officials' crimes and the national law on arrest procedures do not contradict each other, but are complementary," and "the arrest procedure for high-level public officials should follow the arrest law on a sequential basis as a matter of course, not based on the priority between the two laws." However, SAWO did not follow the required order.

Moreover, under South Korean law, if an investigator or prosecutor issues an arrest warrant for high-ranking public officials without permission, they face "detention of up to five million won or imprisonment or detention for up to one year." In this arrest warrant, the judge violated this legal provision.

The lawyer also denied that his client was a ringleader in the alleged coup. According to him, "President Yoon only issued an order to implement an extraordinary measure to block the national parliament. It was a state measure to protect the constitutional order and cannot be called a riot to disrupt the constitutional order." Yoon, argued the lawyer, acted not as a ringleader in a revolt, but as a leader defending the nation's constitution.

Yoon Suk-yeol's Other Ways

However, Im Ghae-gun's allegation, that Yoon had the right to arrest himself because the Special Prosecutor did not correctly follow proper legal procedures, would be hard to verify. On January 2, an arrest procedure expert, who declined to be named due to confidentiality issues, told Beijing Review, "Yoon, if he wanted to, could indeed have arrested himself, in theory. However, there is no evidence showing that he did so in practice."

Nevertheless, Yoon still has several cards up his sleeve that he could use to stay in power. The special warrant issued by the Western District Court does require a proper review before he would be removed from office permanently.

On December 29, the Constitutional Court announced that it would not hold oral hearings on Yoon's impeachment until February as a matter of due process. If the Constitutional Court does not terminate Yoon's presidential power until this February hearing, he would still, de facto, be president in office.

Meanwhile, the National Assembly voted on December 31 to launch an independent National Assembly Special Committee to investigate Yoon, which, however, can only recommend new evidence to the special prosecutor and cannot conduct any investigations itself.

Most importantly, Yoon's presidential immunity means that any investigation by the special prosecutor could be challenged in the Constitutional Court, which has exclusive authority to examine the president.

Yoon's lawyer also claims to have new evidence that would prove his client's innocence. On November 22, his defense team alleged that prosecutors forged evidence against him.

Moreover, Yoon's critics have also questioned whether the South Korean judiciary is independent, given that many key court personnel appear to be Yoon allies. On March 13, 2023, Yoon appointed Cho Han-qyu, the head of the Supreme Court, as acting chief justice after Justice Park Han-chul resigned. According to South Korea's presidential office in a statement, Yoon made this choice because "South Korea is undergoing significant turmoil and challenges." The choice was controversial because Cho, like Yoon, supported Park Geun-hye, South Korea's last impeached president.

On November 7, 2023, South Korean Chief Justice Cho Han-qyu approved an arrest warrant request to have former Democratic Party Chief Lee Nak-yeon detained.

South Korean President Impeached

South Korea's National Assembly voted 220 to 55 on December 14 to impeach Yoon for ordering a police-led paramilitary force to seize his opponents' computers, detain them in the middle of the night and prohibit lawmakers from accessing social media. However, the parliament was denied access to Yoon's computer, denying lawmakers evidence of Yoon's possible collusion with outside groups in planning this attempt. South Korea is a country of laws and evidence, however, not opinions. So, the National Assembly can only claim that Yoon ordered an attempted coup, not prove that he was involved in one. This puts the South Korean parliament in a difficult position to hold Yoon legally accountable for his action and puts the nation's constitution in jeopardy.

According to many observers, Yoon could win a stay of his impeachment for as long his critics cannot prove that he conspired in the planning of this attempted coup. However, the evidence shows that someone in South Korea ordered a putsch this November – but that person, so far, has not been identified and may not be Yoon.

South Korea's political conflict has now entered a critical period. The country's constitution is not only divided between conservatives and progressives but also between the legislature and the executive branch. The constitution, in fact, appears unable to resolve the country's problems. South Korea faces the challenge of re-examining and redefining its constitution in order to meet contemporary political realities, to bring itself up to date.

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Sini

Sini Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link