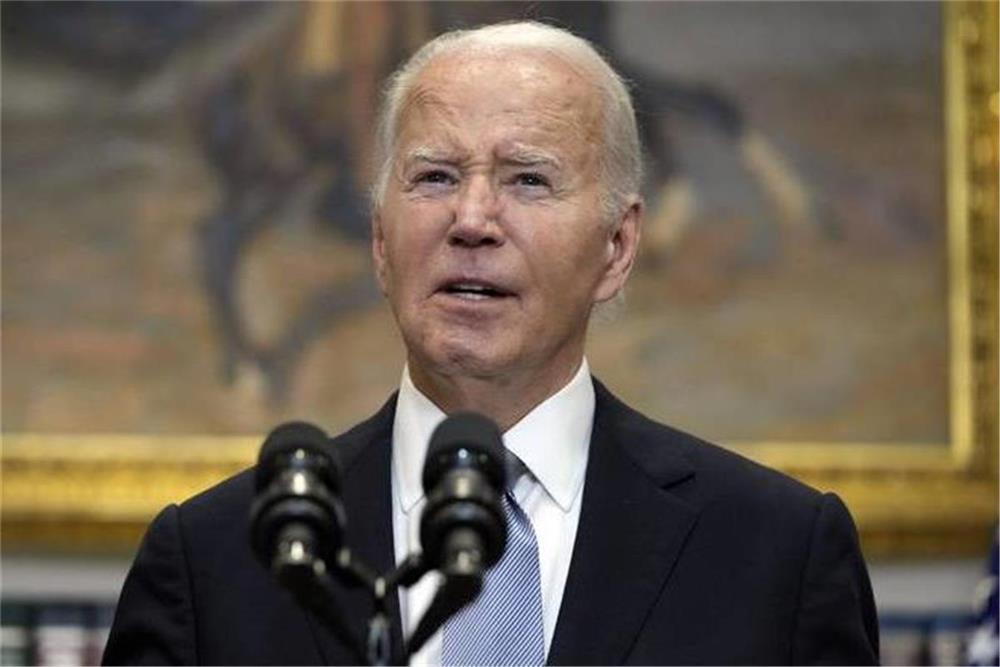

US reports first death from avian flu in humans

Louisiana's health department on January 6 reported the first death caused by infection with the highly pathogenic H5N1 bird flu virus in the United States.

The Louisiana patient, who was older than 65 and had underlying health conditions, became infected after coming into close contact with poultry or wild birds in their backyard. The genome of the flu virus changed in the person, likely leading to the person becoming critically ill. So far, investigators have not found any more related cases.

After reviewing all of the available information about the person who died in Louisiana, "at this time, we still consider the risk to the public to be low and are still conducting our assessment, but the primary reason is that we still have not detected this variant being transmitted from person to person," the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in a statement on January 6.

A wake-up call

The US CDC used gene sequencing to determine that the person who died in Louisiana was infected with the H5N1 virus D1.1 genotype. Sequencing showed that the virus in the person had some rare and concerning mutations. Some of the genetic changes may have happened in the person after the initial infection because they were not observed in the animal source.

"This is concerning – and a reminder that the H5N1 D1.1 virus can change as it infects humans – though if this change had occurred in an animal source of infection or earlier during the human infection, we would be even more concerned. We still have much to learn about this variant and its potential for human-to-human spread or causing more severe disease," the CDC said.

It is unusual to see this particular type of bird flu in the US, but it was also seen in another recent case, in Canada's British Columbia province several thousand miles away. The Canadian case occurred around the same time as the infection in Louisiana, and is also more genetically similar to H5N1 being carried by wild birds migrating south through North America than viruses circulating in domestic poultry. The Canadian case, involving a 13-year-old who was hospitalized, was reported by the local health ministry in November. The teenager has been recovering, but had a prolonged hospital stay and treatment in intensive care in Vancouver.

Public health authorities in British Columbia could not identify a source of infection, but genetic sequencing of the virus showed the variant shared many mutations with viruses that were detected in October on wild birds migrating through the province.

The US CDC has confirmed 66 human H5N1 infections in the country since the start of 2024. Most are considered linked to close contact with poultry flocks and have had very mild symptoms. The CDC said there was no evidence of person-to-person spread of the bird flu viruses. But the death in Louisiana and the Canadian case were different from all the rest because of the genetic makeup of the virus and the seriousness of the illness.

These two cases are "a wake-up call. Both these cases highlight the need for us to take this situation … very seriously," Rajpurkar, a specialist in infectious diseases, emergency medicine, and global health at the University of California at San Francisco, told the science news site STAT. "There is the potential of this virus changing to a more dangerous form."

Another cause of concern is the number of bird flu outbreaks recently reported in poultry in the US, and in a wider range of mammals than has been reported in the past.

APHIS, the part of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) that oversees animal and plant health, confirmed more bird flu outbreaks in poultry on January 6. There were outbreaks in five states, adding to the long list of infections in chickens, turkeys, and ducks.

APHIS also confirmed two new separate cases of bird flu in mammals – both in cats in California. The US government is now investigating an alarming 917 cases of bird flu in mammals, a 40% increase in cases since its last update on January 2, mainly in California. Most of the recently reported cases were in felids, including domestic cats, bobcats, Canada lynx, mountain lions, and an unclassified feline species. APHIS said it is still determining the species for these cats.

In total, these new cases bring the 2023 tally of confirmed mammalian avian flu infections to more than 1,100 in the US. That includes almost 600 cats, as well as otters, mink, foxes, river otters, badgers, and skunks. The CDC is investigating the two people in Louisiana and Canada who appear to have been infected with bird flu viruses that may have come from cats.

H5N1 has been spreading in wild birds for years, and in milk-producing mammals for about a year. In recent years, infections have been found in dozens of mammal species around the world, including seals, ferrets, hamsters, hedgehogs, squirrels, pigs, deer, foxes, otters, weasels, rabbits, badgers, skunks, bears, and humans.

"It's an important reminder the more the virus spreads, the more opportunities the virus has to adapt, the more likely it is to adapt to humans," Malik Peiris, an expert on bird flu at the University of Hong Kong, told the Associated Press. If the virus "becomes well adapted to humans, we should really, really worry."

The threat of a new form of bird flu comes as many countries in the northern hemisphere face a severe flu season. And co-infections in people with both the seasonal flu and bird flu raise the possibility that H5N1 could have the opportunity to pick up the mutations needed to spread easily through human populations.

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Kari

Kari Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link