Washington as Land Speculator

Building a Gentleman's Estate

In the year 1752 Washington made his initial land purchase, acquiring 1,459 acres of land along Bullskin Creek (in modern-day Frederick County, Virginia). This acquisition marked the beginning of the second phase of his cartographic career, during which he functioned as a land surveyor for private clients and also as a land speculator. Over a fifty-year period he would continue his cartographic work by seeking out, purchasing, surveying, and settling properties in various locations. In 1800, his will contained a list of 52,194 acres in his possession at the time of his death in Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, Kentucky, and the Ohio Valley. In addition he also owned property in the form of lots in various cities and towns, including Winchester, Bath (now Berkeley Springs, West Virginia), and Alexandria, Virginia, and the newly created City of Washington.

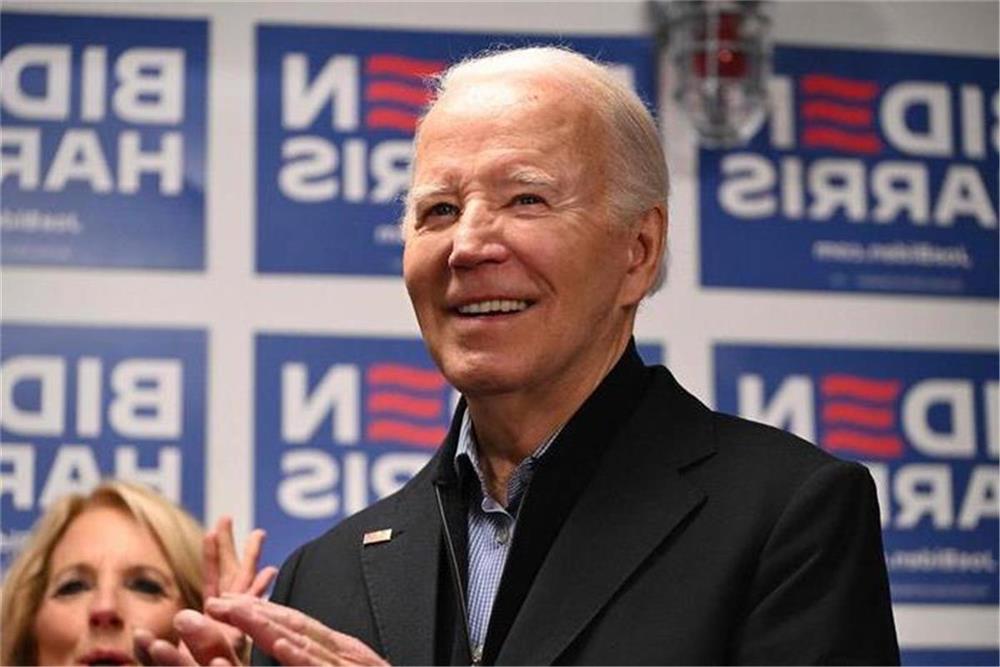

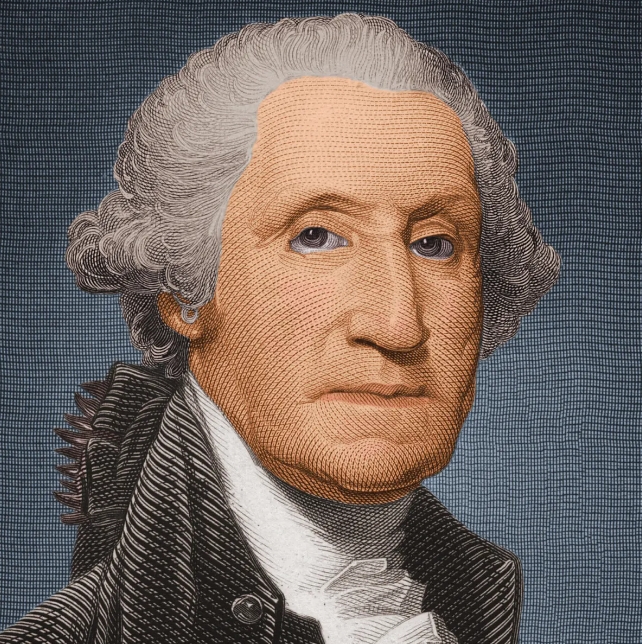

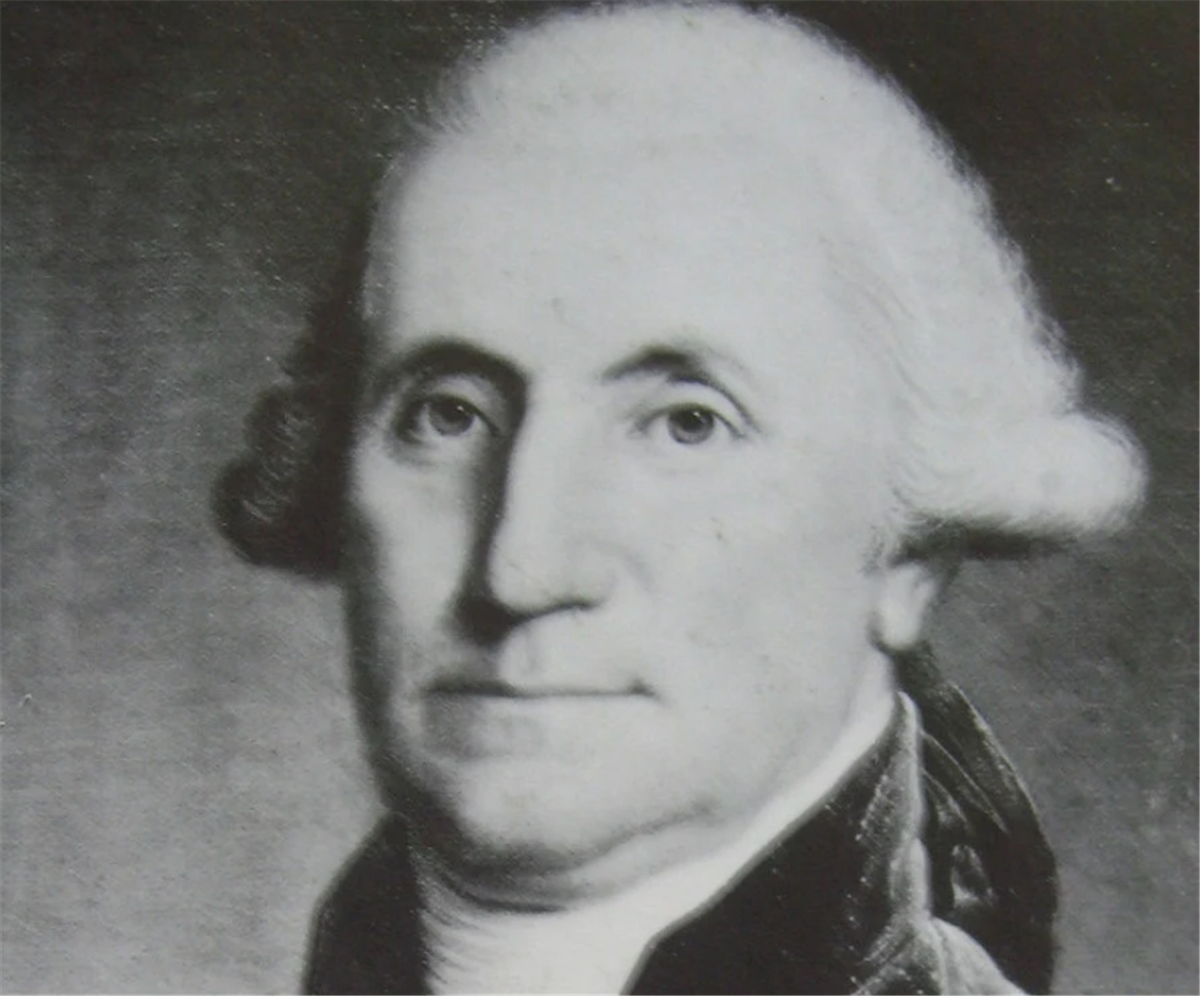

In 1758 Washington left military service and returned to a private life. On January 6, 1759 he married Martha Custis, a wealthy widow with two children, from a neighboring plantation. Almost immediately upon returning to Mount Vernon, Washington began to make improvements on his new estate, and it was not long before he sought to enlarge it even further. In 1760, his neighbor, William Clifton, approached Washington with an offer to sell him a 1,806-acre tract of land located along the Potomac River on the north border of Mount Vernon for the price of 1,150 sterling. The two men, who were friendly rivals, began negotiations on the matter, but before they could complete the deal Clifton agreed to sell the tract of land to another of Washington's neighbors, Thomson Mason, for 1,214 sterling. Despite a binding agreement to sell to Washington and a series of angry letters, Clifton backed out of the deal. Eventually Washington paid the higher price, 1,250 sterling, to secure the land for himself. This area became known as the Washingtons' River Farm.

Shown here are two maps of the Clifton Neck Lands that are among the earliest surviving maps of individual farms at Mount Vernon. The first is a map that Washington copied in 1760, probably during the course of purchasing the property. Entitled, Plan of Mr. Clifton's Neck Lands from an original by T.H. made in 1755 & Copied by: G. Washington 1760 it includes the survey courses and distances of the perimeter and of each field under cultivation on the tract. The plan also includes a lengthy list of persons working the property. Seven years later Washington prepared a map of a much smaller portion--846 acres--between Little Hunting Creek and the smaller Poquoson Creek, entitled A Plan of My Farm of Little Hunting Creek.

The Union, Dogue Run and Muddy Hole farms lay to the north of the Mansion House farm along Dogue Creek. They too were added to the estate through land purchases. In 1762 and 1765 Washington purchased two tracts along Dogue Creek from his friend George Fairfax (son of Lord Fairfax) for £360 sterling each. In 1766 he acquired 300 acres along the Little Hunting Creek from the widow Elizabeth Reed. This tract adjoined and enlarged the small area that Washington had purchased in 1748 to form the initial 267.5 acres that made up the original Mount Vernon Estate. Washington's personal involvement in surveying and mapping the lands along the Potomac and its tributaries, and the use of survey plans in the purchase of his own lands, are evident in these and numerous other surviving maps held by the Geography and Map Division.

Washington did not lose interest in the maintenance and management of his land while serving as General of the Continental Army and as President of the United States. Between 1786 and 1799, he exchanged approximately thirty letters with Arthur Young, a supporter of agricultural improvement in Britain. Young and Washington were kindred spirits in the search for innovative methods of crop rotation and scientific approaches to the breeding of farm animals. Washington was a particularly keen student of the various stages of crop cultivation as they were affected by climate change, as evidenced by his letter of August 26, 1793 to Young, in which he enclosed a map of his lands and described the acreage under cultivation at each of his five farms: Union, Dogue Run, Muddy Hole, Mansion House, and River. Washington also outlined the crops growing at each location: tobacco, wheat, corn, potatoes, barley, rye, clover, buckwheat, beans, hemp, and flax. In his capacity as a scientist and cartographer, Washington was not merely reporting facts to his correspondent. He had created a map of his farms that was specifically designed to illustrate the distribution of particular crops at specific locations.

Western Lands and the Bounty of War

Washington's involvement in surveying and mapmaking, and his desire to accumulate personal landholdings beyond those of his Mount Vernon estate and other farm properties in Virginia, made him deeply interested in the issues surrounding land speculations. The controversy over the distribution of military bounty lands is but one example of Washington's advocacy of his fellow veterans' cause and his own aggressive pursuit of large-scale land claims.

At the outbreak of the French and Indian War, Lt. Governor Dinwiddie issued a proclamation on March 5, 1754 designed to encourage enlistments in the colonial militias for the war against the French. Besides their pay, those who enlisted in the Virginia Regiment raised under the command of Lt. Colonel George Washington were also promised a share of two hundred thousand acres west of the Ohio River. As it turned out, however, the Virginia soldiers who had fought with Washington in the Braddock and Forbes expeditions against the French at Fort Duquesne would not see these bounty lands for another twenty years, after Washington had led the fight to secure their title.

In the year 1763, the formal conclusion of the Seven Years' War--the worldwide war between Britain and France--brought hope that the military bounty lands would soon be granted. These hopes were dashed with the issuance of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (among its provisions, it forbade colonial governors from issuing patents for land grants west of the Allegheny Mountains). Washington nevertheless moved ahead, as suggested in the following letter to William Crawford, a Pennsylvania surveyor:

I can never look upon the PROCLAMATION in any other Light (but this I say between our selves) than as a temporary expedient to quiet the Minds of the INDIANS, & that it must fall of course, in a few Years, especially when thos very INDIANS consent that we shd. possess the same Lands. Wherefore any Person who neglects to hunt out good Lands, and in some Measure mark and distinguish them, from other People, to the End that they may be able to possess them--will never regain them. Upon this Principle I beg leave to trouble you to find out and survey for me the best Lands upon the Ohio and its Branches, that you can. When you shall have found the Place desired; you may blazed the Trees, or make some other distinction of the Land, that People may know it to be taken up; as the Indians are as well acquainted with these Parts as We are: If you will be at the Trouble of Hunting out the Lands, I will take upon me the Part of securing them as soon as there is a Possibility of doing it and will moreover, be at all the Expence and Charges of Surveying and Patenting the same. . . . You must know that my Int

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Jerry

Jerry Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link