Why Clinton Survived Impeachment While Nixon Resigned After Watergate

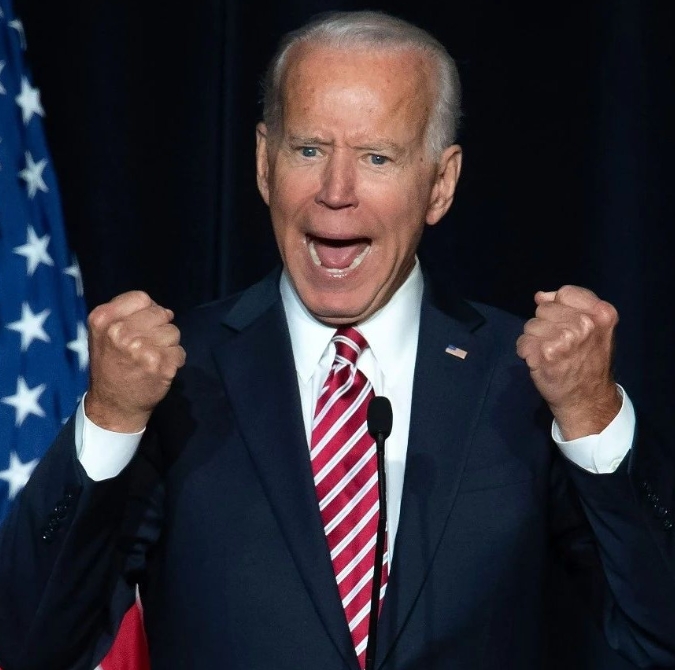

So, why wasn’t Monica the scandal that led to the first sitting president’s resignation and impeachment?

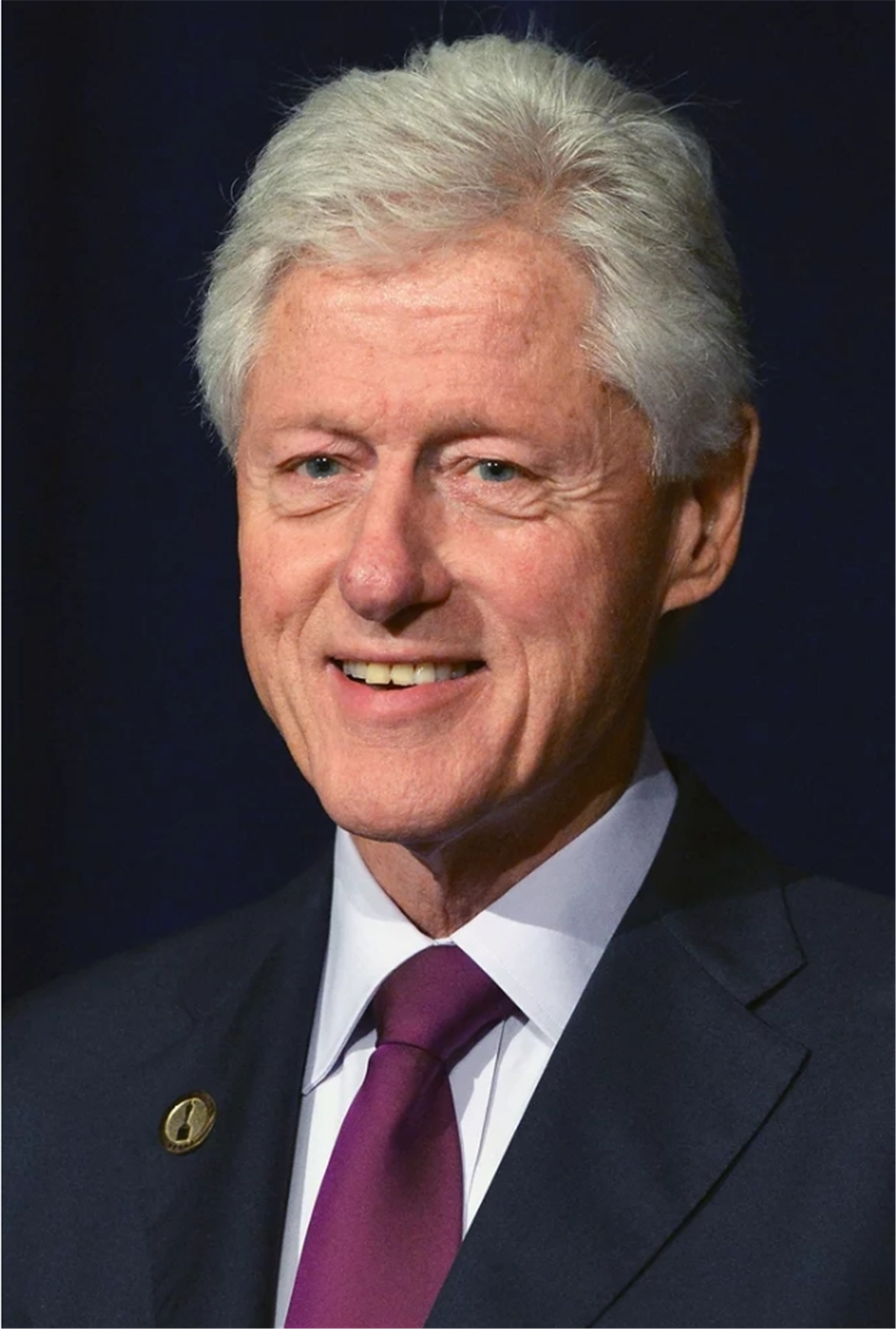

The short answer is because it wasn’t Watergate, says Brandon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston and the host of the podcast, “Party Politics.” “No other presidential scandal in American history even compares with Watergate in severity and breadth,” he says.

But, let’s take a deeper dive.

For starters, Nixon resigned in 1974 while Clinton was impeached and acquitted in 1999.

“With the advantage of historical perspective, it is clear that the Nixon and Clinton scandals were different in fundamental ways,” says Scott Basinger, associate professor of political science at the University of Houston.

Then there’s the fact that Clinton survived the impeachment process—though his party feared he wouldn’t, Rottinghaus says—because voters didn’t have that same fear.

“They didn’t really want him impeached. His approval ratings were high. The economy was booming,” says Lara Brown, director and assistant professor of the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University.

Johnson aside, that era was an important factor in what happened to Nixon and Clinton, Brown says.

“One of the important realities of our history is that Watergate came on the heels of the Vietnam War. The difficulties of the war—the large loss of life combined with the sense that the war was unwinnable—and the Pentagon Papers—where many of the public realized they had been ‘lied to’ about the war—contributed to the decline of trust in government that began in the latter halves of the 1960s. This is evident in the polling.”

During Clinton’s presidency, unlike Nixon’s, Brown notes that trust in government was increasing.

“When Nixon was president, trust in government was very low—around 25%, and it continued in that range. For Clinton, trust in government was growing during the 1990s—it bottomed out at the beginning of that decade with the Iran-Contra scandal and was about 25% then, too.”

Some of that rise in trust, she says, was related to the productiveness of Clinton’s working relationship with the Republicans in Congress.

“In essence, people were pleased that legislation was passing and compromises were being made across the aisle, from balancing the budget to welfare reform. This was in sharp contrast to Nixon’s relationships with Congress.”

Plus, adds Rottinghaus, Watergate was the culmination of years of scandals and events.

“Watergate wasn’t a single event that happened and everyone was shocked by it. Rather a lot of different bad things happened, a lot of different things got covered up. There was a lot of back story that was uncovered over years, not months. And once the truth was uncovered, Nixon was in deep trouble and his resignation became inevitable,” Rottinghaus says. “So, the outcome of the resignation of the president was surprising but not shocking.”

The economy also was important, Brown says, citing a struggling economy in the early 70s while the economy was strong for Clinton and his job approval ratings continued to increase in the late 1990s.

“And when economic downturns happen, presidents take the blame for it,” Brown says. “Again, Clinton was on the other side of this trend. The economy was growing, not contracting. And when the economy does well, presidents are credited with it.”

Rottinghaus says the economy also was a strong factor in the survival of Bill Clinton, with voters reluctant to turn an incumbent president out of office during a booming economy with low unemployment rates.

Party unity also was a factor, Rottinghaus says, with Nixon gradually losing the support of his Republican allies while Clinton maintained relatively strong support from his Democratic allies in Congress, even conservative Democrats like Joe Lieberman.

“And Clinton was able to garner bipartisan support in the evaluation of his job performance,” he adds. “Whereas years of Watergate had eroded President Nixon’s base of support to just core allies. This meant that the House and Senate Republicans were willing to turn out Nixon as a part of the party’s long-term political interest, whereas Democratic support for Clinton helped prevent impeachment from occurring in the Senate.”

And, he adds, there was the betrayal of Nixon’s allies.

“The scandal brought down a lot of Nixon’s allies,” Rottinghaus says. “He had a lot of people who supported him and enabled his wrongdoings.”

Basinger agrees, saying that Clinton’s “co-conspirators” were more limited—he and Betty Currie as compared to the numerous Nixon aides and government officials involved in Watergate.

Plus, Basinger says, the scandal was different in type, too. “This was not an abuse of power scandal—it was a personal immorality of a sexual nature rather than an abuse of political power,” he says.

What’s really fascinating to me is how public opinion changed during the year in which the Lewinsky scandal was the most prominent news story,” Basinger says. “Initially, Republicans and Democrats shared the opinion that if Bill Clinton had had sexual relations with Miss Lewinsky then he should be impeached. Where they really differed was in their assessments of whether or not Clinton had had the sexual affair that he was accused of having.”

Over time, Basinger notes, Republicans and Democrats agreed that Clinton did have an inappropriate sexual relationship with Lewinsky, “but their opinions about the reasonable punishment for that violation diverged.”

“Republicans thought that he should resign or be removed from office, and Democrats did not have that opinion,” he says. “This division also extended to public assessments of Clinton’s lying under oath and his attempt to commit an obstruction of government.”

Democrats, he says, were more accepting of the idea that there were special circumstances that surround lying about sex that would not lead to support to remove him from office.” It seems that the context was important—that it was related to sexual relations,” Basinger says.

Brown, who lived through the scandal as a Clinton campaign staffer, says the root of the Clinton scandal was an extramarital affair—which most people felt was a personal scandal and a private matter. “People felt that what happened in ‘98 was not a political issue and did not affect Clinton’s presidential job performance,” she says.

They really resented Ken Starr for going so far afield—the initial mandate for the independent counsel was to investigate Clinton’s involvement in the Whitewater real estate development,” she adds. “Most people felt that the Paula Jones lawsuit and what was understood to be a consensual affair with Monica Lewinsky to be Clinton’s personal business and that he was doing a stellar job as the president.”

In today’s #MeToo environment, she says it seems unlikely that Clinton would have survived the vote in the Senate on his removal. “But at the time, the country had peace and prosperity and they felt that Clinton was doing a good job as the president. They did not want to see him removed from office. They did not want to see him impeached,” Brown says.

Both men faced impeachment and lengthy investigations while in office. But there was a wide disparity in their approval ratings after their respective presidencies—66% for Clinton; 24% for Nixon.

“President Nixon’s approval and greatness ratings improved slightly over time, but the stain of Watergate and his resignation will always serve as a ceiling to rise even higher in the ratings,” Rottinghaus says. “President Clinton gets credit for a strong economy, maintaining a peaceful world order, and thus his legacy will always have a bit more room to rise in the ratings. However, a reevaluation of the power imbalances in personal sexual relationships and the #MeToo movement will likely hurt Clinton’s overall rise in the rankings of great presidents.”

And, Brown adds, it’s important to note that, in general, expectations for the institution of the presidency and for the person of the president were also very different in the early 1970s than it was in the late 1990s.

“People felt the presidency was a lofty—above the people—kind of institution. Camelot, if you will,” she says. “And they expected the president to be ‘better than’—smarter, more trustworthy more moral (than the general public)—during Nixon’s time in office than they did in the 1990s, when they wanted the presidency to be accessible and they wanted presidents to be more compassionate, relatable and authentic.”

And, she says, Clinton’s personal foibles had been revealed during his campaign (Gennifer Flowers, draft dodging and experimentation with marijuana, for example).

“And so, people were surely less surprised by the Clinton scandal than they were of Nixon’s crassness and apparent meanness, which was revealed in the tapes of his private White House meetings, but he had not displayed that in public,” Brown says.

Famous Persons

Famous Persons English

English

Jerry

Jerry Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Pinterest

Pinterest Linkin

Linkin Email

Email Copy Link

Copy Link